~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hellraisers Journal, Thursday January 16, 1908

Monongah, West Virginia – Hunger Reigns with Breadwinners Dead

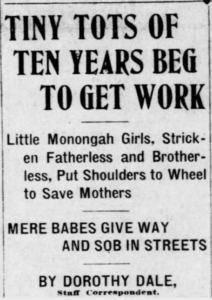

Who among us could ever forget the following from journalist Dorothy Dale reporting from the devastated town after the great mine disaster:

Please letta me work, lady; gotta getta money…Please you get something for me, I can do.

A little hand touched my arm. The curl-framed face of a girl of 10 years looked into mine.

[She said pitifully:]

You know mans all dead. Boys all dead. Only girls left to work.

From The Labor World of January 11, 1908:

WIDOWS AND ORPHANS CRYING FOR BREAD

—–

Entire Burden of Every Industrial Disaster Falls

Upon the Poor Wage-earners’ Family.

—–

Bread Winners Killed By Wilful Negligence of

Their Employers, the Union Smashers.

—–

In the appeal issued by the Monongah Relief Committee it is stated that of the 3,000 inhabitants of Monongah the mine disaster destroyed one-half of the breadwinners. Two hundred and fifty wives, 1,000 children and many unborn children are left without means of support. The company has declared that the families occupying these houses may remain in them until other provision is made for them and in other ways has been generous in its attitude, but it states that operations cannot be resumed at the damaged mines until these houses are available for the new force. $200,000 is asked for by the Relief Committee to meet these needs. Commenting on the situation Paul U. Kellogg, special representative of Charities and The Commons, says:

The statement of the case made in the appeal is not too strong. Putting the average wage at $50 a month (which was given me as fair), an income of $20,000 a month has been cut off from this working population— $240,000 a year. There will not be so many mouths to feed by one-fourth; but in the face of this loss, the real significance of where the burden of industrial disaster falls, stands out. And the character of the town stands out. This is not a community. It is not paying its way. It uses the well and strong. It is part of the working plant of the coal industry. Sympathetic and kindly as may be their sufferance for the weeks following the disaster, these broken families must move away, as surely as the bodies of the men who supported them had to be removed from the mine offings, so that the work could go on.

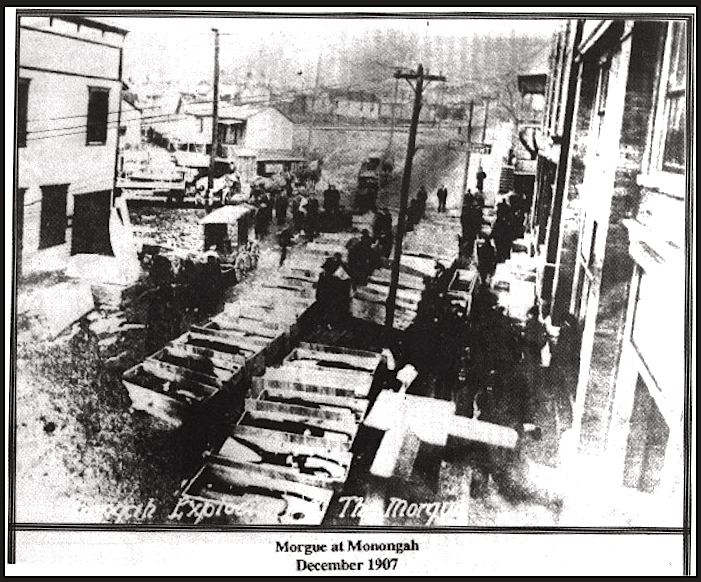

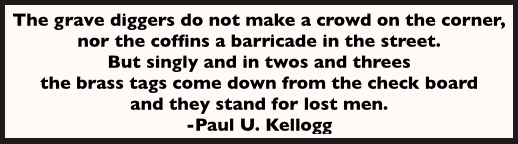

“My God, there are not enough washings in this town to care for a hundred widows,” said an old Irish woman to me, “nor boardin’ houses.” For those, in the fair days of the town, had been the wages of a workingman’s death. The explosion, the bunching of the loss in a single valley, only serve to cast into stronger relief this antithesis of the coal pits and the community. The woman who has motherhood enough in her to cling to her children must start life fresh at a deficit, to herself and whatever community harbors her. It makes no essential difference whether she is one widow, or one of a hundred. After all, then, is it such a far cry to maintain that the mines shall pay their way—that through some adequate form of tonnage tax or workingmen’s compensation, and liability group insurance among the operators, the burden shall be borne by the industry—and hence the unpreventable part of it, in the long run, by the consumer. For there is not always this fierce claim on the public’s sympathy. There is not always this thunder of a hundred trains. There is not the “all cry” of the town’s women together. The grave diggers do not make a crowd on the corner, nor the coffins a barricade in the street. But singly and in twos and threes the brass tags come down from the check board and they stand for lost men.

———-

[Photograph added.]

SOURCE

The Labor World

“Only Labor Paper in Northern Minnesota”

(Duluth, Minnesota)

-Jan 11, 1908

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn78000395/1908-01-11/ed-1/seq-1/

IMAGES

Monongah MnDs, Tots Beg for Work, Ptt Prs, Dec 10, 1907

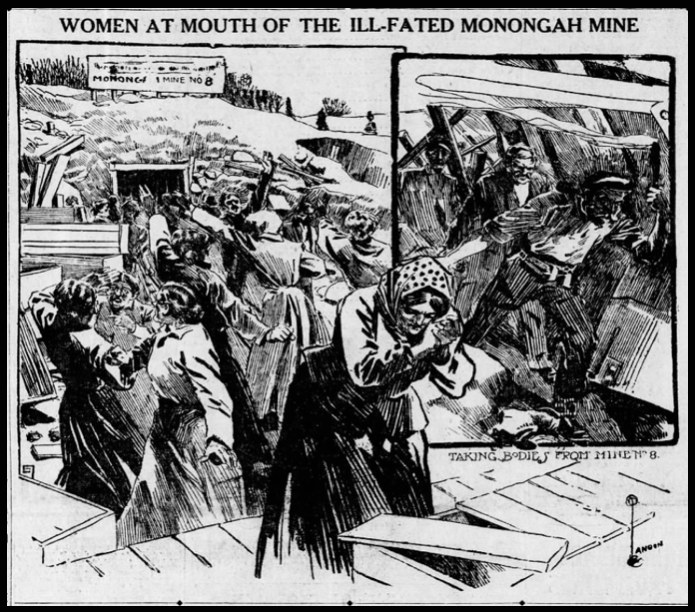

+ Monongah MnDs, Women at Mouth of Mine, Ptt Prs, Dec 10, 1907

https://www.newspapers.com/image/142132645/

Monongah MnDs, Morgue, Dec 1907

http://www.wvgenweb.org/wvcoal/mono.html

See also:

Hellraisers Journal, Wednesday December 11, 1907

Monongah, West Virginia – Little Orphan Girls Beg for Work

Little Girls, Orphans of Monongah, Beg for Work: “Please letta me work lady; gotta getta money.”

Tag: Monongah Mine Disaster of 1907

https://weneverforget.org/tag/monongah-mine-disaster-of-1907/

Tag: December 1907 (Most deadly month in history of US coal mining.)

https://weneverforget.org/tag/december-1907/

Charities and the Commons:

A Weekly Journal of Philanthropy and Social Advance, Volume 19

Publication Committee of the

New York Charity Organization Society, 1908

https://books.google.com/books?id=oCYrAAAAYAAJ

C&C Jan 4, 1908

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=oCYrAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA1305

“Monongah” by Paul U. Kellogg

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=oCYrAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA1313

According to Kellogg “the company,” responsible for the deaths of 362 breadwinners, was “considered liberal” because:

It has never put a widow out of a house; if necessary it has sheltered her family as much as a year; has given her a chance to make a start at washings, or set her up in a boarding house, and required men to patronize her: or it has given her children employment.

The fact that those children would have to leave school in order to accept the company’s kind offer to sacrifice childhood and become little breadwinners, is not mentioned by Kellogg.