You ought to be out raising hell.

This is the fighting age.

Put on your fighting clothes.

-Mother Jones

Hellraisers Journal, Sunday August 27, 1916

Mesabi Range, Minnesota-“To Hell With Such Wages!”

From The Survey of August 26, 1916:

When Strike-Breakers Strike

The Demands of the Miners on the Mesaba Range

By Marion B. Cothren

[Part I]

THE strike-breakers of 1907 have become the strikers of 1916 in the iron mines of Minnesota. Coming over in boatloads from south eastern Europe nine years ago and hired by the United States Steel Corporation to break the iron strike called at that time by the Western Federation of Miners, these polyglot nationalities speaking thirty-six different tongues have become Americanized in the melting pot of the Mesaba mines. Today Finns, Slavs, Croats, Bulgars, Italians, Rumanians, have laid down picks and shovels and are demanding an 8-hour day, a minimum wage of $3 for dry work and $3.50 for wet work in underground mines and $2.73 in open pit mines, abolition of the contract labor system, pay-day twice a month.

The last of May, so the story goes, Joe Greeni, an Italian employed underground in the Alpena mine at Virginia, Minn., opened his pay envelope to find a sum much less than he had under stood his contract called for. “To hell with such wages”, cried he, throwing his pick in the corner, whereupon he vowed never to mine another foot of ore. Second thought, however, convinced Greeni, that action was deadlier than inaction. For three days he stayed at his post, going from stope to stope, saying, “We’ve been robbed long enough, it’s time to strike!” Then he left for Aurora to begin agitation at the extreme eastern end of the range in the little St. James’ mine with its force of 40 miners.

On June 3 Joe Greeni saw the effects of his revolt. The St. James’ mine struck and the flames of discontent soon ate their way across the entire range from Aurora to Hibbing. Long lines of miners, halted occasionally by mine guards and deputy sheriffs, wound their way over the 75 miles of mountain road which connect the ten-odd towns of the Mesaba Range, and passed the word “strike” from place to place.

Beginning at Aurora this procession, sometimes augmented by children and wives wheeling baby carriages, gained in numbers as the men from the different mine locations joined in. In this way, say the mine owners, were the men “intimidated” to leave their work; in this way, say the miners, were their fellow workers given courage to revolt against long-standing grievances of low wages and a vicious contract system. [See The Survey, September 7, 1912.]

Gradually the spontaneous uprising became organized, the Industrial Workers of the World who had held one or two meetings along the range in April were called upon to direct the strike, and Carlo Tresca, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and other I. W. W. leaders were sent from Chicago to advise the local committee. The Western Federation of Miners, an American Federation of Labor organization, has played no part in the strike, but the State Federation of Labor affiliated with the A. F. of L. has endorsed the strikers’ demands.

Unlike other great mine strikes, living conditions and working conditions are rarely mentioned in the committee meetings of the strikers or in the speeches of the organizers. In the midst of this network of mines producing 60 per cent of the iron ore of the United States, flourishing little municipalities have grown up, each with its own elected mayor and other officials, and with populations ranging from 2,000 in Buhl to 15,000 in Virginia.

Here the miners have the advantages not of paternalism but of enormous taxes wrung from the Steel Corporation property, and supporting school houses excelled by none in the country; well stocked libraries, and streets paved in the most approved manner, lined with beautiful trees and illuminated by clusters of electric lights, which make the “great white way” look pale and gloomy!

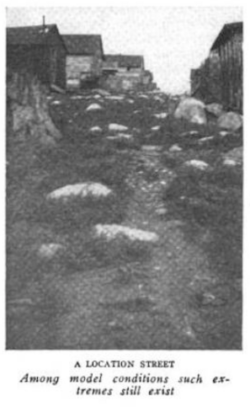

Just a stone’s throw from these spotless towns lie the mines and the “locations” or settlements of miners’ homes. Some of the men own both the land and the one, or two-story frame house upon it; others build their own houses on leased “company land”; still others live in company houses or boarding homes on the company property. But while dwellings vary from modern little structures with well kept grounds to unspeakable shanties in filthy surroundings such as exist in the Carson Lake location, there is nowhere the interference with personal liberty and restriction upon social relations which aggravated the Colorado coal miners’ strike. Indeed, the social life of the towns enriched by the cooperative spirit of the Socialist Finns, who form about 15 per cent of the 12,000 miners, is particularly free and democratic. In almost every town is a hall or opera house owned by the Finnish Socialists, as well as cooperative stores, cooperative baths and cooperative boarding houses.

Likewise, the working conditions in both underground and open pit mines although difficult are on the whole fairly good. The report of the inspector of mines of St. Louis county for 1915 states that there were only 24 fatal accidents and 28 serious non-fatal accidents among the 11,346 employes of the 120 mines.

In a word, it is not against the social or industrial conditions, be they bad or be they good, that the 6,000 striking miners are protesting (the I. W. W. leaders place the number out at 8,000, the employers at 3,000) but against the contract system with its alleged graft, favoritism and resulting low wages.

In the open pit mines, employing about 50 per cent of the men, the miners receive $2.60 for a ten-hour day. They are demanding $2.75 for an eight-hour day, a difference which in itself might be settled amicably.

[We will conclude this article tomorrow with Part II.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SOURCE

The Survey, Volume 36

(New York, New York)

Survey Associates, 1916

https://books.google.com/books?id=yK9IAAAAYAAJ

The Survey of August 26, 1916

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=yK9IAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA530-IA3

“When Strike-Breakers Strike” by Marion B. Cothren

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=yK9IAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA535

IMAGE

MN Iron Miners Strike, Location, Cothren, Survey, Aug 26, 1916

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=yK9IAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA535

See also:

A Footnote to Folly:

Reminiscences of Mary Heaton Vorse

-by Mary Heaton Vorse

Farrar & Rinehart, 1935

Chapter IX Mesaba Range

https://books.google.com/books?id=sKhAAQAAIAAJ

Note: Mary Heaton Vorse traveled to the Mesabi with Marion Cothren.

She stated: “Marian [Marion B.] Cothren with an assignment

from the Survey, went with me.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Fire in the Hole – Hazel Dickens