You ought to be out raising hell.

This is the fighting age.

Put on your fighting clothes.

-Mother Jones

Hellraisers Journal, Monday October 30, 1916

Washington, D. C. – The Brotherhoods and Adamson Act

The October edition of the International Socialist Review published two articles regarding the Railroad Brotherhoods and the Adamson Act, which we have re-published in today’s Hellraisers, see below. President Wilson signed the Adamson Act into law early in September just in time to prevent a national railroad strike set to begin on Labor Day.

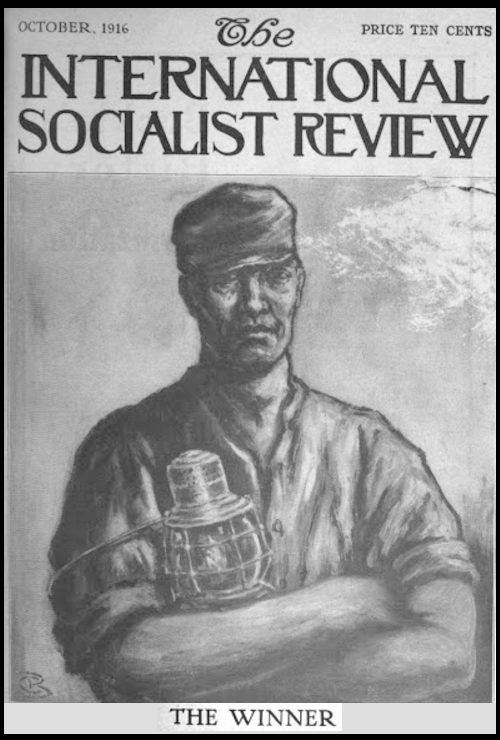

From the cover of the Review, October 1916:

The threat of a strike compels Congress to take action:

WHY THE RAILS WON

By MILITANT

FOR the first time in the history of the United States, organized labor by threat of physical force action has compelled the national congress to come across with legislation. This is the big outstanding fact of the clash between the four railroad brotherhoods and the railroad companies, with their dispute brought to the doors of the federal government for settlement.

Whether the legislation demanded and obtained will result in material benefits to the railroad workers is yet to be seen. If the eight hour law enacted by congress does not end up with higher wages for the freight trainmen and freight enginemen of the United States, then another chapter of fierce railroad history must be undergone. It may not go as easy all round as it did in August and September of 1916.

Next year the passenger trainmen and passenger enginemen of the United States have their contracts with the railroads expiring. The passenger service employes are to make fresh contracts in the same period of time in which the railroads will be on trial as to whether they will obey the eight-hour laws now enacted by congress. The outlook is that all the solidarity of ranks and direct simplicity of demands which distinguished the four united brotherhoods in the summer of 1916, will again be to the front in 1917.

Let no one mistake. The experience of August, 1916, went deep into the blood, bone and marrow of the railroad brotherhood organizations. Scabs were detected. Many of that dirty, detested breed known as “company men” were caught with the goods, caught with their false faces off, identified as fakes in their presumed loyalty to the brotherhoods, and marked for their dependability in possible strikes. The prophecy of Eugene Debs a few weeks before the crisis that the companies count on a large percentage of scabs among “old and tried loyal employes,” and among firemen who have ambitions to become engineers, was shown to be a true prophecy in those first few days of September when the railroad managers expected a strike, were ready for a strike, and polled their workers and lined up and signed up those who would scab on the jobs of strikers.

If a big rail strike is written in the cards and dice of destiny—if a great transportation tie-up is due at some future date next year or the year after, the loyal men of the brotherhoods are better equipped for it than they would be if the August, 1916, crisis has not been passed thru. They have the numbers and names of the deserters, the victims of the itching palm and the celluloid backbone, who can be figured as failures and fizzles if a showdown struggle is called for.

Again let no one mistake. The railroad managers were ready for a fight. Thousands of engineers and trainmen were called to inside offices and talked to in a brotherly and fatherly way and asked to stand with the companies if a strike came. Recruiting offices for strike-breakers were opened. Big ads were run in daily newspapers. The daily papers, for years fed with railroad advertising appropriations and owned by railroad capitalists and railroad banks, splattered their pages with stuff intended to poison the public mind against the outrageous anarchists who are going to block rail transportation from coast to coast. Yes, the rail managers were ready for a long hard grapple. Then came President Wilson with the declaration that the eight-hour workday is sanctioned by the sober judgment of society and his farewell to the railroad presidents, “God forgive you—I never can.” Then came congress, house and senate, passing the eight-hour law.

In its essence it says that the railroads of the United States must from January 1, 1917, pay their freight train conductors, brakemen, engineers and firemen the same wages for eight hours that now prevail for ten hours, and all overtime must be on a pro rata basis. The original demand of the brotherhoods for time and a half for overtime was waived by them in their demands on congress. Punitive overtime as a principle was thrown overboard. What was gained was a uniform wage raise of about twenty per cent—and an increased confidence in the value of physical force tactics. The punitive over time principle must come into practice on the railroads before the theory of the eight-hour day is ever actually in working effect.

This is recognized well by the aggressive minority of thinkers and agitators in the railroad brotherhoods who were active in bringing about the crisis just passed. One way or another must be found for the organized railroad workers so that the companies will be punished with increased wage expense whenever a railroad man is worked more than eight hours of twenty-four. The next crisis comes when the day is at hand for the railroads to live up to the wage increase provided for by the federal eight-hour law. If, by trickery of lawyers and courts, the railroad companies are able to defeat the purpose and intent of the eight-hour law, all the forces inside the brotherhoods which were ready for a nation-wide transportation tie-up early in September, will be again ready for direct action.

One secret chapter in this rail history of the summer of 1916 is yet to be written. Some kind of a message was sent by President Wilson thru some sort of reliable go-between to the railroad presidents and capitalists. They knew whether or not the president stood ready to seize the roads, grant the eight-hour day, and run them under government management. The mobilized militia of the nation, sworn into service on the Mexican border, was available for action in backing whatever the president notified the railroad managers to be his wish. Whatever Wilson’s stand was in this respect, it was a factor in the ensuing settlement.

In the highbrow philosophies of our day is a thing called “pragmatism.” It means doing what you want to do when the nick of time and the proper moment has arrived in the process of evolution for doing that thing. The freight handlers at Chicago and other points have long wanted to organize. The Big Four brotherhoods in their exclusive and aristocratic craft organizations have never gotten to the point of helping the freight handlers organize. Their motive has been to let the freight handlers take care of themselves. So on the big day when it looked like a rail strike was sure to come, the organized freight handlers walked out and presented demands on a number of roads. They won out and established organizations on some roads, failing on others.

They called the bluff of the rail barons on arbitration and showed the country that Hale Holden, president of the Burlington, and other officials are only noisy prattlers on “arbitration.” It was shown that the railroad managers are awfully ready for arbitration, will shed salt tears for the beautiful principles of arbitration, when a powerful combine like the Big Four is making demands, but arbitration gets a kick in the rear buttock and goes out the door into the alley if it’s a weak, minor union like the freight handlers’, which is asking for arbitration.

The cry for arbitration that went up from the capitalists’ organizations, from newspapers and from pulpits, was a weird chorus. The United States Chamber of Commerce, a Rockefeller-controlled machine organized by Harry Wheeler, a Chicago banker shown in the U. S. Industrial Relations Commission-Rockefeller-Ivy Lee correspondence to be a Rockefeller tool, was one organization that shed tears for arbitration. Various manufacturers’ bodies who regularly choke off labor unions before there is any chance for organization, also wept for arbitration. Victor Lawson’s Daily News in Chicago, which four years ago was autocratically absolute in its denial of arbitration in the pressmen’s lockout, in cartoons and editorials wept for the betrayal of arbitration. To some of us with eyes and ears for the present and with definite recollections of the past, it was all as incoherent as a mixed quartet sung by traveling salesmen at four o’clock in the morning in wet territory after months in a dry state.

Once more, let no one mistake. The magic of arbitration is passing. The bunk of arbitration has been argued by mouth pieces whose declarations have gone nation-wide. Never again can arbitration as a principle for settlement of labor troubles get the old standing it had a year ago or ten years ago. New principles, new methods, must come into practice. It has been discovered that arbitration is a game at which those win who are able to employ the slickest talkers and the slickest manipulators. The statisticians and argufiers and deliberators are only so many pieces and pawns moved back and forth in a puppet show. And the master hands and the master money bags behind the show are dark forces able to win at arbitration.

That the most powerful, commanding, conservative, strategically situated labor unions in the United States should now come to the point where they specifically tell the nation that they are forever thru with arbitration as a method for settling disputes of wages, hours and conditions, is probably one of the most significant single developments that has come to the front in recent years.

In his rarely keen series of articles in the Masses, Max Eastman, on “Towards Liberty,” says the governmental forms of the future are “a shadow of mystery.” That is, we don’t know where we’re going but we’re on the way. It is true, for instance, that the Big Four railroad brotherhoods are aristocrats and their doors of membership and affiliation are barred to the trackmen, shopmen and shovelmen. And the Big Four stands aloof from the American Federation of Labor. They are by themselves. They walk alone. They have special reputations and seem to wish freedom from the social stigma newspapers and pulpits attach with discredit to “union labor.” Engineers and trainmen hold themselves above hod carriers in the social scale, as Clarence Darrow pointed out in a speech to an intelligent minority of them at a meeting in Chicago. One Louisiana engineer wrote to the Locomotive Engineers’ Journal last year suggesting that railroad engineers belong not to a craft, but a “profession,” and something should be done to give engineers a standing as “professional men” alongside doctors, preachers and lawyers.

And yet, tho there is an aristocratic spirit among the railroad brotherhoods, there is also no doubt but that their way of fighting and their achievement of demands is a big push of progress for the whole working class. A strict analogy applies between the Big Four this summer challenging the railroad kings and the English barons of King John’s day. The barons were not the working class of England. But the barons broke the power of the king and made that power a lesser thing than it was. And the upshot of it was that certain rights of human beings, all human persons, came to be more clearly defined and upheld. The whole English working class by this process of aristocrats breaking in on the king’s power came to have rights of habeas corpus and rights of the ballot which they did not previously enjoy. Similarly, the rights of human beings, all human persons, to have an eight-hour workday has been advanced to a measureable extent this year thru the action of the labor aristocrats who got it written into national law for the benefit of a select few of the working class.

The Big Four brotherhoods take in only eighteen per cent of the total railroad workers. The remaining eighty-two per cent was not in on the negotiations. Their time is to come.

[Paragraph breaks added.]

Will the Adamson Act prevail?

THE RAILROAD WORKDAY

By FULLSTROKE

Evansville, Indiana, Courier of September 5, 1916

THE nation-wide strike of the four labor organizations in train service being set for Labor Day, September 4, has given a new meaning to that national holiday. All these years since its institution, Labor Day has had little real significance other than to show by parades that labor, on the whole, was happy. Now like a thunderbolt right out of the blue came this proposition, catching up with and passing anything this continent ever contemplated, like the pay car passing a tramp.

Still it is understood amid the superior brains who are in control of things that the railroad movement for an eight-hour day has been neatly sidetracked somewhere at a backwoods station where no tracer will be able to find it. For in the last hours of waiting for something to happen, the manufacturing and shipping interests got into the game to save their own hides, pried congress loose from its moss-backed dignity and there was enacted in Washington what you might call a hurry up scenario. Not that congress was willing to make any move at all, but for a short time it did go some. The so-called Adamson Bill was passed almost at the last hour, a bill which the labor committee left at the national capitol said would be satisfactory. And the strike was called off.

This Adamson Bill is certainly a peach as bills go. In the first place it provides that on railroads eight hours shall constitute a day’s work, which is just an ordinary amendment to labor schedules previously in force. However, being a law instead of a signed up agreement and as it carries no provisions for a penalty when violated, it may be considered a joke even as a law. The next section provides for ten hours’ pay for the shortened work day.

Stop for a minute and think what would happen to any law which might provide for the small matter of compensation for labor where a corporation is concerned, when that law comes before a court. The United States Supreme Court is, if anything, a far more conservative body than congress itself, but if that provision in the Adamson law ever gets before that outfit, the way it will be kicked down stairs and across the street will place judicial dignity among the lost arts of past ages.

Lastly the law takes effect January 1, 1917, date far enough after the national election to permit any old party politician to safely add his kick to what is expected will be already dead, without visions of himself in the class of the lame ducks.

As far as law goes, this one may be considered as a first class joke. President Ripley of the Santa Fe has already stated thru the press that his road will pay no attention to the law, which is about the position of all railroads on any law, and they should not be expected to make an exception of this one. Just what position the roads will finally take, it is too early to state, except that their conception of law and order appears to be normal, which is that it is something for the working class to swallow, while it remains invisible to the corporation lords.

Still the roads are going to accept it and without much of a fight. There will be the usual gag and splutter about taking the somewhat bitter dose, but it is going down after a fashion. For behind the enforcement of the Adamson law stand 400,000 men, militant at least on this one question of the eight-hour day, and those men hold a strategic position in modern industry which it is far better for the masters to have them remain unconscious of as long as possible. Then also there is another rate raise, for the rates have not been raised now going on a year and a half.

This idea of any section of labor really getting even a part of a rate raise is what startles the adapt. Never before has it been deemed necessary to give it a thought even after using the argument to the limit for acquiring the raise. But just now the gentle art of rate raising cannot get by without it. Lastly it insures the private ownership and control of the greatest cinch ever worked upon the unthinking multitude, at least until the next social shake-up. So the railroads are going to come down to the eight-hour day in the very near future, not as a basis of a maximum work day, but as a matter of pay.

What makes all this noise that is driving out the chimney swallows is not the eight-hour day, but the time and a half for overtime. That is the thing which, from now till the end of the swindle will stick and hang. And by the term “end of the swindle” is meant the end of private ownership and control of railroads. All the genius and power behind the game is to be turned loose on that part of the demand, with probabilities that the men will lose. Railroading as conducted at present postulates starting with all tonage in sight and robbing every siding for the next sixteen hours along the right-of-way. With time and a half paid for over time, it surely will increase the pay roll and then some. To get a train over the road would be an unpardonable violation of the sacred memory of Jim Hill, or whoever it was that made this method of train operation the standard.

But something has been gained right here. The sacred principle of arbitration is gone among these workers and gone forever. The social patchers are now searching for a substitute, but what can be done with workers rather critical on the source of whence these things come? In a world governed by certain laws of evolution perhaps to get rid forever of arbitration is all that can be expected of one move. The ground will be soon cleared for the next step, and that is due soon.

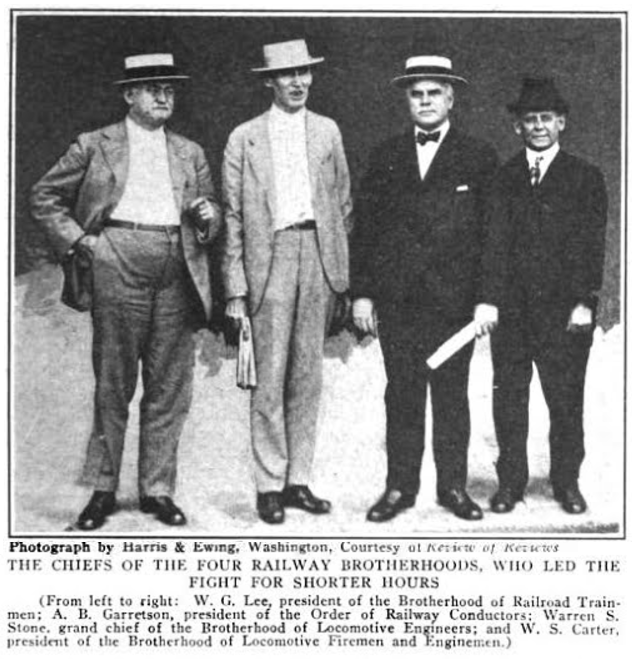

[Photograph and paragraph breaks added.]

SOURCS

History of the Labor Movement in the United States Vol. 6

On the Eve of America’s Entrance Into World War 1, 1915-1916

-by Philip S Foner

International Pub, 1982

Chapters 9 & 10

https://books.google.com/books?id=nIQFAQAAIAAJ

The International Socialist Review, Volume 17

-ed by Algie Martin Simons, Charles H. Kerr

Charles H. Kerr & Company,

July 1916-June 1917

https://books.google.com/books?id=SVRIAAAAYAAJ

ISR Oct 1916

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=SVRIAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA195

“Why The Rails Won” by Militant

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=SVRIAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA199

“The Railroad Workday” by Fullstroke

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=SVRIAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA237

IMAGES

RR Worker, The Winner, ISR, Oct 1916

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=SVRIAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA191

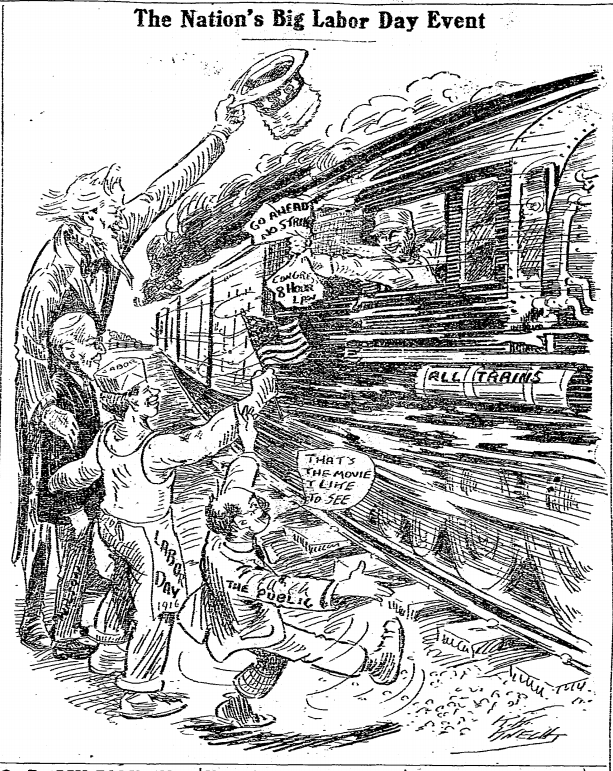

RR Workers, Victory Train, ISR, Oct 1916

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=SVRIAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA199

RR Brotherhoods, Leaders, ISR, Oct 1916

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=SVRIAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA201

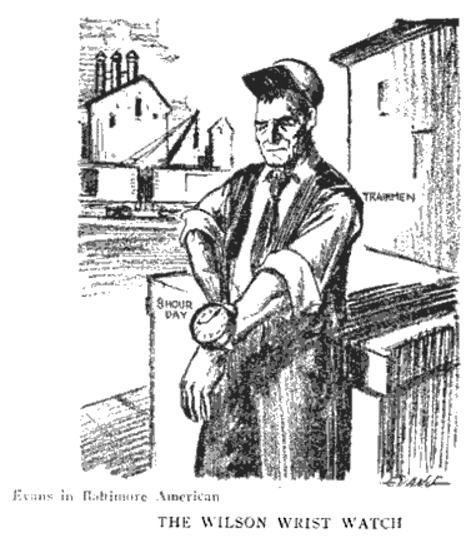

RR Worker, Wilson Wrist Watch, ISR, Oct 1916

https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=SVRIAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&source=gbs_atb&pg=GBS.PA202

Labor Day 1916 & Adamson Act, Evansville IN Courier-1, Sept 5

http://www.genealogybank.com/

See also:

Adamson Act

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adamson_Act#cite_note-4

Wilson v. New 243 U.S. 332 (1917)

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/243/332/

“Handlers Vote General Strike,”

Chicago Daily Tribune, Oct 30, 1916

Note: unable to find exact name of freight handlers’ union, more research needed.

http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1916/08/30/page/1/article/handlers-vote-general-strike