~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hellraisers Journal, Wednesday December 19, 1906

From The Labor World: Young Lives Ground Up for Profit

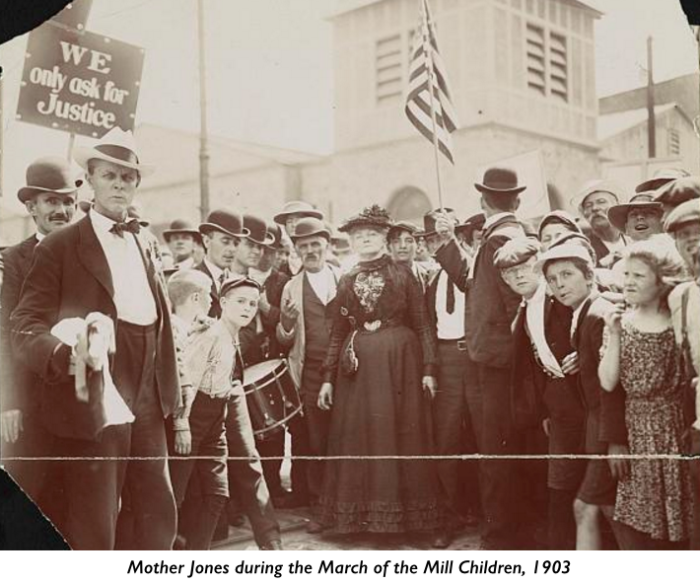

Mother Jones has never forgotten the cruelty of Child Labor since the summer of 1903 when she led the mill children of Philadelphia on a march to Oyster Bay. They made the long trek in the summer heat in order that they might tell President Roosevelt about the hardships of their lives spent at work instead of in school. The President refused to meet with the children and Mother takes a few jabs at the “Great Prosperity” President in the following article on the subject of Child Labor in the American South.

BABY WAGE-EARNERS IN

SOUTHERN MILLS

—–“Mother” Jones Writes Stirring

Article on Iniquities of

Child Labor in South.

—–

Cotton Mills Produce a Type of

Children Easily Recognized

As Most Puny.

—–(By “Mother” Jones.)

After thirteen years of absence I returned to see what improvements had been made in the industrial conditions of the mill workers of the sunny south.

I found that there had been marvelous progress made as far as the mills and machinery were concerned. Looking at the advancement in that line, one would think that the day of rest for the workers must be near. Instead of bringing rest and leisure to the workers, however, this perfected machinery brings only a more merciless exploitation than was ever practiced before. With the advancement in machinery has come a corresponding advance in the methods of exploitation. That is all the difference the improvements have made upon the workers.

I stood one morning in the early dawn and I watched the slaves as they entered the pen of capitalism. I could see the shadows of the slaves passing along in the brush to the mill at twenty minutes to six in the morning. Children, roused from the heavy sleep of youth, left their beds reluctantly and entered the institution of capitalism to create wealth for others to enjoy.

The mill at Graham, N. C., has been built but four years. In that time they have doubled the size of the mill and its machinery, and in addition to this they have paid forty per cent dividends to the stockholders each year.

I watched the workers, young and old, who had produced all this wealth, when the machinery stopped at noon. They returned to the shack which they call home, scraped together what was left from breakfast, ate it for lunch in a mad hurry, and then they drifted back again to their posts. It brought to my mind the tread-mill punishment with which the tyrannical government of England tortured her victims only eighty years ago. These mill children are allowed only forty minutes for dinner. Then they stand before that iron giant until twenty minutes of seven at night. I asked myself what progress had there been in the conditions of these workers? I saw only tragedies everywhere. The lives of the men, women and children who produce the clothing, for the people of the land are living tragedies. Under the mill-skies of Massachusetts hearts are breaking from overwork and poor food, just as they, are under the mill-skies of the sunny South. So exhausting is the work that something must be done to combat the existing state of affairs. The workers are old long before they are old in years. They are old before they have had a chance to get their growth. The machine has become almost human and the child has become a machine.

In Columbia, S. C., a splendid illustration of benevolent feudalism may be observed. On one side of the streets is a great mill, occupying a whole block. Up the street is the school building. Opposite is the church with its steeple pointing up to the throne of God to proclaim the wonderful work being carried on in His name. Nearby, too, is the repair shop, called the “accident ward.” Here baby fingers are amputated and mangled arms and legs and broken heads are repaired, with what care and skill the company doctor sees fit to call to his aid. The thought in the mind of this mechanic, the doctor, is to adjust the living bolts and to so repair the throbbing, fevered parts, that the machine may go back again to the mill to create more wealth for the master. If the case is too badly injured to give promise of service, little interest is taken and it is simply a case for the junk-heap of our industrial life.

If there happens to be something the matter with the “morals” of these living machines, the services of the sanctified machinist are called into activity. With threats on one hand of eternal hell and on the other hand of eternal blessings, to play the golden harp in the world beyond, this moral mechanic does what he can to render this member useful in creating wealth. To those of us who would better these conditions these sky pilots say, “Your thoughts and plans are of this earth—worldly. Mine are higher, they point upward; they are ‘other worldly.’ I point from this world as it is to the heavenly world which is to repay the poor for their suffering if they bear it in patience now.” And for centuries the poor deluded workers have been kept from their birthright here, but they are waking up.

The work of making the clothing for the world’s inhabitants is now so highly specialized that children do most of the spinning while the weaving is done by men and women.

A suck shuttle loom pays the weaver fifteen cents per cut for twelve hours’ work. In order to make wages the worker must watch several machines. “When everything runs smoothly,” said a woman who is far above the average in intelligence and skill, “I can make a dollar and fifty cents a day. But you know things don’t always go smoothly. And it is hard for a woman to stand on her feet thirteen hours every day. We can’t stand it all the time, and so $1.60 is more than the average weaver gets.”

In the spinning rooms the children are paid ten cents on an average for watching a “siding.” Some very nimble little ones manage to take care of eight sidings, but they are physical wrecks in a few years. The whirr of the passing threads becomes a part of their whole mental and physical make-up. I saw a little boy dying of typhoid fever, and in his ravings he was tying the knots of the spindles. “On, I wish I’d get another siding!” he was crying. “This don’t work, and boss will be mad and I will lose my job.” In his death struggle this little child felt the sword of the capitalist over him. This little victim of our brutal system died and the “new siding” which the fates had in store for him could not have been as cruel as the one he left behind for his little brothers to watch.

The cotton mill produces a type that can’t be mistaken anywhere. An under-sized boy, a narrow chest, a shifting and uncertain gait, an expressionless face, and a soul that hopes not, for there is nought in the cotton mill worker’s life but the long hours of toil, repulsive food, bare walls, and at the close a hole in the ground.

Death can hold no horrors greater than their lives have known.

The mill owners are not only the employers of labor, but they are landlords, the merchants, the school directors, the patent medicine venders and the Salvation Army soul-savers. On every side of him the worker feels the “touch” of his employer.

As school director, for instance, the infamy of the employer’s greed blocks the pathway of the future of the little child. A rule is made and strictly adhered to that a child who is absent a certain number of days during a term can not be promoted into the next higher class, even though the studies have been carefully kept up and the child is ready to take an examination to prove his fitness for promotion. The hard and fast rule is carried out from year to year and at last parents and children, too, become discouraged and the door of the school house closes behind the child and the mill door swings open to receive its prey, never to give it up until death seals its ears to the whirr of the spindles and the looms. During the last session of the legislature in South shorten the hours of labor from twelve to ten. The mill owners got a few of their workmen before the legislative committee who made a plea for the “business’ interests.” They insisted that they could not make a living unless they ran at least twelve hours per day. The bill was pigeon-holed. To make sure of its case the company sent a petition around the mill district asking the voting mill hands to sign it for a continuance of the twelve-hour day. I saw a man prepare to sign it, but his wife said, “No, ten hours, even is too much!” “But we’ll lose our job!” he cried in dismay. “I tell you even ten hours is too long to spend in those pens!” she insisted and the man did not sign. Mothers have far more of the revolutionary spirit than have fathers when it is a question of life and comfort for children. It will be a better day for the labor era, when the voice of the mothers may be heard in the legislative councils of the land.

South Carolina passed a law prohibiting the employment of children under the age of twelve. As always happens, the mill owner stood by and out of the kindness of his heart, made provision for the children of the widow and of the invalid or the unfortunate. This admits all but the children of the well-to-do. In many cases the parents have turned out exploiters and have sworn that they were unable to support their children.

During my stay in Columbia lately a boy of nine fell into an elevator shaft and was killed. His mother drew his pay. The press statement declared the boy to have been above the age of twelve and insisted that he was not in the employ of the company that day. On such technicalities the employer evades the law.

A shrewd scheme shows the mill owner as landlord. He will not rent his tenements or his cottages unless the family can furnish a worker in the mill for every room in the dwelling.

“Teddy had to go to work,” said one mother sadly. “We had four rooms, and when I was kept at home with the baby, Teddy had to go to make four hands from this house of four rooms!” The rents are low for these company houses, making it an inducement to fulfill the requirements of the landlords. They range from $1.50 for single rooms to a family domicile for six dollars per month.

One of the large mills in Columbia is owned by an employer who owns mills in Fall River, Massachusetts. He has opened this mill in the South because he can manufacture goods so much cheaper, and then he sends the goods to the north to compete with his wretched workers there. Since the strike of 1904 the Fall River workers are living on a starvation wage.

I sat each night watching the weary procession of men, women and children leaving the mills at 6:45 p. m. There were old men walking with canes, mothers with babies at their breasts, and many young children who should be playing with balls or with dolls in the train of weary marchers. On the streets of Fall River I noticed from day to day that there were many little white hearses carrying the baby victims to the hole in the ground. I discovered that these baby lives had been insured by the parents and that the undertakers collected the insurance money.

I thought, were it possible for these little ones to hold a convention-a national convention of mill and mine and factory slaves, what tales of brutality their ghastly little faces would tell without words.

While our race suicide president was making the rounds of the southern states, boasting about our national prosperity, he was speaking of the forty per cent dividends which the life blood of these little ones was creating for the stockholders. The subject of child labor, which is the real race suicide, was not mentioned in the florid, boastful speeches. Our good president does not see that there are those among us who have no boasts of such prosperity. We see that in the days to come we shall look upon this devastation and this ruin of a people as a ghastly crime, and we shall wonder why the people stood for it and why they cheered him? A French statesman once said: “Let our self-seeking and our ambitions die. Let our names be forever buried, but let the cause of the people live!”

As I looked upon the blight which the whirr of this machinery cast upon the minds and bodies of these baby workers, I concluded that a sound race either in body or in mind cannot be expected from such environment. The child coming from parents who entered the mills themselves in childhood must be the product of this environment of overwork.

We are at the parting of the ways. We have to choose in regard to a continuation of the system that produces high dividends and yachts and automobiles, palaces, banquet halls and monkey parties for the one class who do no useful work-and in order to maintain them in their debauchery, we have to pay for a constabulary and police to shoot us down; we build orphans’ homes for our children reform schools for our bad boys, slum tenement for our homes, while we have a “job,” and penitentiaries, insane asylums and soup kitchens for ourselves when we are out of a Job. The police club us into submission. Injunction machines on the bench defend the exploiters and prevent us from teaching the workers a higher, nobler civilization.

Again I say, we have come to the parting of the ways. We have reached the time when we must choose sides. How shall the future see the crisis through which we are passing?

I stand for the overthrow of a system of commercial piracy which destroys the home and prostitutes human life. I stand for a higher manhood, for a happy childhood and for the abolition of every infamous institution that interferes with the rights and liberties of a great people. Which side do you stand on, citizen? Do you stand for justice and human rights, or for commercial piracy as we have it today?

This is no age for palliators or for cowards. You will have to take your stand on the one side or on the other. I stand first, last and all the time for the rights of the working people.

SOURCE

The Labor World

(Duluth, Minnesota)

-Dec 15, 1906

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn78000395/1906-12-15/ed-1/seq-1/

IMAGE

Mother Jones March of the Mill Children, 1903, with text

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2015649893/

See also:

Hellraisers Journal: Mother Jones on Child Labor & Children “shriveled and old before their time.”

http://caucus99percent.com/content/hellraisers-journal-mother-jones-child-labor-children-shriveled-and-old-their-time

Hellraisers Journal: Mother Jones on Hideous Conditions Of Child Slavery in Southern Cotton Mills

http://www.caucus99percent.com/content/hellraisers-journal-mother-jones-hideous-conditions-child-slavery-southern-cotton-mills

DK tag: March of the Mill Children

http://www.dailykos.com/news/TheMarchoftheMillChildren

DK tag: march of the mill children (sorry for the 2 different tags.)

http://www.dailykos.com/news/marchofthemillchildren

Theodore Roosevelt’s theory of “race suicide” can be found in this speech given in Washington on March 13, 1905, before the National Congress of Mothers:

http://www.nationalcenter.org/TRooseveltMotherhood.html

Theodore Roosevelt, Political Cartoons concerning “Race Suicide” Controversy

http://www.theodore-roosevelt.com/toonsbytopicracesuicide.html

We will sing one song of the children in the mills

They’re taken from playgrounds and schools

In tender years made to go the pace that kills

In the sweatshops, ‘mong the looms and the spools

Then we’ll sing one song of the One Big Union Grand

The hope of the toiler and slave

It’s coming fast; it is sweeping sea and land

To the terror of the grafter and the knave